“Do you know what ‘Sputnik’ means in Russian? ‘Travelling companion’. I looked it up in a dictionary not long ago. Kind of a strange coincidence if you think about it. I wonder why the Russians gave their satellite that strange name. It’s just a poor little lump of metal, spinning around the Earth.”

…

“And it came to me then. That we were wonderful travelling companions, but in the end no more than lonely lumps of metal on their own separate orbits. From far off they look like beautiful shooting stars, but in reality they’re nothing more than prisons, where each of us is locked up alone, going nowhere. When the orbits of these two satellites of ours happened to cross paths, we could be together. Maybe even open our hearts to each other. But that was only for briefest moment. In the next instant we’d be in absolute solitude. Until we burned up and became nothing.”

Both of these extracts come from Haruki Murakami’s Sputnik Sweetheart, the beautiful and tragically sad tale of unrequited love and existential emptiness.

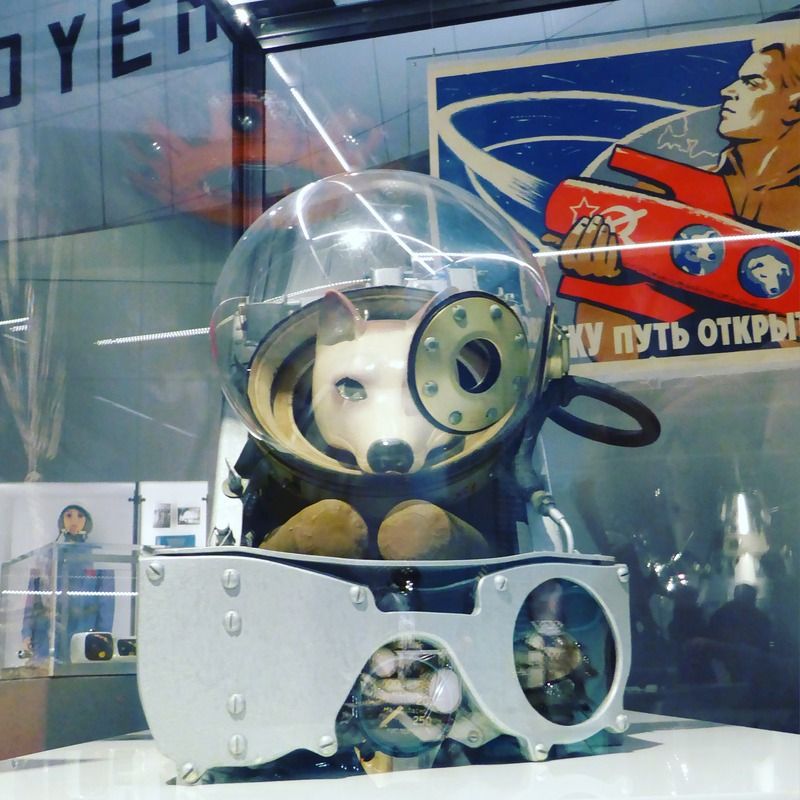

I read the book, coincidentally, shortly after visiting the Science Museum, and let me make this perfectly clear, the Cosmonauts exhibition is inspiring, beautiful and wonderful. But it’s also frightening and sad. When I saw Sputnik 2, and the model of the capsule where poor Laika had the dubious honour of becoming the first mammal in space, I clutched my own chest, forcing myself to not shed a tear, and imagined the poor stray, who had been ‘rewarded’ for her obedience and intelligence, expiring in the emptiness in the cold, dark silence of space, without anyone to comfort her, without any chance of returning home to the handlers who no doubt missed her and mourned her as soon as they locked her in the capsule. Space is cruel, and progress is cruel.

The exhibition celebrates the success of the Soviet Union’s dominance in the space race, until at least 1969 when Kennedy landed the cold war coup of the century, literally on the moon.

Until then though, the American’s languished behind the scientific creativity and genius of the Soviets. Led by their Chief Designer Sergei Koralev they streaked ahead. First satellite, first man in space, first woman in space, first spacewalk, they ticked off successes whilst the Americans struggled. It was only when Koralev died that the Americans really caught up and the funding partially dried up in the USSR.

The exhibition is a celebration of the space race, Sputnik is of course commemorated. The “Beep… Beep… Beep” it generated is plastered all over one wall. The Russians thought little of the launch of Sputnik, it had a small passing reference dedicated to it in the official Soviet newspaper Pravda, but when the rest of the world caught sniff of it, the story exploded and the Soviets realised they had a massive propaganda victory. I remember the tale of the American who happened to be in Moscow when Sputnik was launched. He was relentlessly teased in the street with Muscovites making the “beep” sound at him. And I love how Koralev wanted Sputnik 1 to look beautiful, because one day he knew it would be housed in museums around the world. Truly it is an iconic marvel.

Three of the Cosmonaut heroes are also celebrated.

Yuri Gagarin

“I saw for the first time the Earth's shape. I could easily see the shores of continents, islands, great rivers, folds of the terrain, large bodies of water. The horizon is dark blue, smoothly turning to black, the feelings which filled me I can express with one word, joy.”

The first man in space, Yuri Gagarin, with his handsome film star looks was a global superstar. After surviving space, he sadly died piloting a prototype plane, which immortalised him forever as the tragic and beautiful youth. He had a huge following, and the first country he visited outside of the communist bloc was The UK. Although he sat next to the Queen on an official dinner, his visit was instigated through an invite by the Amalgamated Union of Foundry Workers in Manchester, he himself had been a steel worker before joining the military. Massive crowds followed him everywhere and little anecdotes such as him refusing an umbrella to show solidarity with the crowds getting rained on won him hearts. He was the darling of the press, even the right wing press.

The other thing to note about Gagarin, is he was tiny, perhaps only 5’3”. I assumed he would be tall, but cosmonauts were partially chosen (aside from the gruelling mental and physical fitness they endured) on their size, they needed to fit in the capsules to take them into space.

Gagarin and Leonov (source Russia Today)

Alexei Leonov

Leonov was the first man to conduct a space walk. I remember watching a BBC production on Cosmonauts and he talked candidly about how he avoided disaster when he nearly didn’t make it back to the spacecraft.

His suit had slowly expanded due to the pressure, which meant his hand had slipped out of the expanding glove and he couldn’t grip to climb back to the safety of the Voskhod 2. Had his ship swept beyond the sun and orbited into the darkness, the cold would have killed him instantly. He only had minutes. He took a risk to save his life, he slowly vented air from his suit into space and although suffering from the bends, he mercifully was able to get his hand into the glove and climb back into the craft. The phlegmatic Leonov didn’t want to make a fuss so didn’t mention the issue to base while he was trying to save himself.

But he and his crewmate Belyayev had another brush with death on the same mission, the module the cosmonauts were on, landed hundreds of kilometres off course, and for two nights they endured sub zero temperatures waiting to be rescued. To airlift them they needed space for a helicopter to land, so the cold ravaged men on board had to ski with their rescuers to reach a point where they could finally be safe.

Leonov was, or rather is, a romantic, an artist and we’re lucky he’s still with us to regale us with his tales of adventure and joy at seeing the birth of the day from the dark crescent rim of the Earth. He was a painter, and on each of his missions he would draw and this tiny little exhibit was one I was particularly fond of. His pencil set, with wrist ring and individual threads for each pencil (to stop them floating off) and his little painting “The Rising of the Sun” March 18th 1965. Those are the pencils he used.

“I have had two dreams, to be a pilot and an artist – I succeeded in achieving the former and became a cosmonaut. But not the latter. Still, all my spare time I dedicate to painting”

Valentina Tereshkova

“Anyone who has spent any time in space will love it for the rest of their lives. I achieved my childhood dream of the sky.”

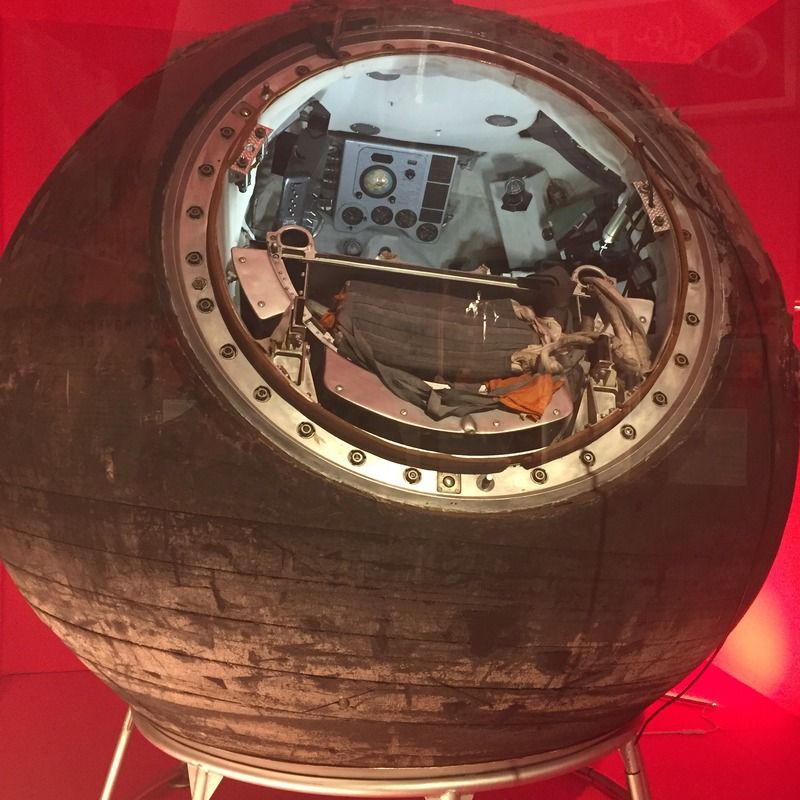

In 1963, Valentina Tereshkova (calling sign “Chaika” – Seagull in English) became the first woman in space, orbiting 48 times over 3 days, clocking up more time in space than all the American astronauts put together up to that point. The former factory worker was selected with four other women from over 400 applicants and from those five, she was the only one who made it to space, it took nearly two decades for another woman to achieve the same goal. As well as being the first woman in space, what made her ascension to the space programme even more remarkable was that she was the first civilian to make it. She was given an honorary title in the Soviet Air Force during her training. The Science museum has two of the most precious artefacts on display. Her flight suit with the striking dove of peace emblematic on her chest, but also the actual module she flew into space in, from Vostok 6. The solid looking dented old sphere must’ve been so tiny in the depths of space.

Still alive, the fiercely patriotic Tereshkova had volunteered, as recently as 2013 to go on a one way space mission to Mars.

War and Peace

Many of the biggest scientific breakthroughs come through military funding. At the height of the cold war, space engineering and advancement contained the implied threat of nuclear war. If you can launch a rocket into space and land it fairly accurately, then you can attach a warhead to it and obliterate your enemies. And falling straight down, it’s almost impossible to disable.

Thankfully the doomsday clock did not strike midnight during the cold war, and the old enemies, the USA and the main power rising out of the ashes of the Soviet Union, Russia, have a tense but less antagonistic relationship.

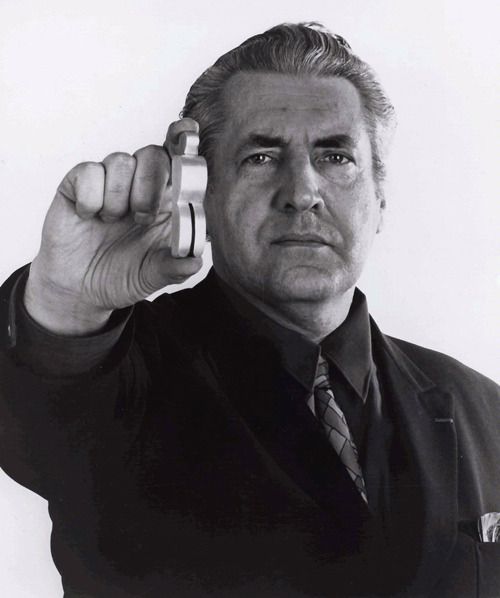

Many of the space missions are collaborative affairs now, genuinely science based, multi-country and a standard for international cooperation and friendship. Even in the height of the cold war, the respect between Astronauts and Cosmonauts and their respective governments was genuine. In 1971, the Apollo 15 mission left a small sculpture by Paul Van Hoeydonck on the Moon for “the fallen astronaut” commemorating the deaths of both American and Soviet travellers.

The artist with a replica of “the fallen astronaut” from his website. (not part of the exhibition)

And in 1975, the artist and dreamer Alexei Leonov, in his second space flight, commanded the Soviet half of the joint Soyuz – Apollo mission, where the Soviet craft would dock with the American Apollo craft commanded by Thomas P. Stafford in a symbolic act of union to commemorate the thawing of relations, the end of the cold war and the end of the golden age of the Space Race. Leonov of course drew portraits of both sets of crewmates.

Zond 7 and the tribute to Gagarin

The final room of the exhibition is dedicated to Zond 7. In 1969 the Soviets sent an unmanned spacecraft around the moon with a mannequin onboard, equipped with various sensors around its body, to measure radiation levels, as a pre cursor to a planned moon mission. The mannequin’s face was based on the image of Gagarin. It’s a beautiful serene space washed with blue and pink light. The Soviet’s never made it to the moon, but the American’s did.

Cosmonauts – at the Science Museum until 13th March 2016.