This post contains spoilers – please do not read if you want to read the book in the future!

I finally got round to reading The Buried Giant by newly crowned Kazuo Ishiguro. Although aware of his work, it was my first novel of his that I’d read and I have to say I found it compelling and interesting. And after being slightly bemused by where the story was headed, and I have to say, I didn’t like many of the characters at times, it came to a great conclusion which left many questions unanswered. It’s readable, addictive, with a gentle prose like delivery.

The story is set in the early Dark Ages, that is, shortly after the fall of the Roman influence (around 400 – 600AD), and from a historical context, it would be true to say that little documentation remains from that era, or was written centuries after the events that allegedly took place.

What we do know is that the Christian (Romano) Britons and the newly arrived pagan Saxons (who would become the modern day English), live together side by side. Ishiguro captures this well, and adds the omnipresent weight of the understanding that more and more Saxons were arriving on the eastern shores of Britain and spreading west, squeezing the Britons into smaller and smaller territories.

However, this is an alternate, fantastical Britain being depicted, drawing heavily on the myth and legend of these islands. Fierce and stupid Ogres roam the land, sometimes stealing children. Pixies hide in forests and rivers, beguiling travellers. Boatmen adopt a Charon like role, ferrying passengers to an idyllic island where they will live in happiness but may not necessarily see another person. Although not common, sorcery is respected and feared. Monks allow crows to shred their flesh to absolve themselves of sin, carrying the guilt of people. And an old dragon spews a mist over all the surrounding lands which has a strange calming effect on the residents, both Christian and Pagan, making them struggle to remember their pasts and memories. Although this magic relating to the dragon’s breath isn’t revealed until later in the book.

Ishiguro also draws from the chivalrous romances of Arthurian legend too, and in the Buried Giant the Romano-British King Arthur has died some years, possibly decades, before. This was after leading a great victory against the Saxons and an uneasy peace treaty is in place between the Britons and the Saxon invaders/settlers. This combination of history, fantasy, myth, legend and romance was also successfully blended in the underrated film Excalibur by John Boorman and there were many times reading the book, where I was reminded of that movie.

So that’s the backdrop, what about the story?

The story revolves around two characters, a husband and wife Axl and Beatrice. They are old, they are tired, but they are devoted to each other and in love. They live on the outskirts of a warren like village community in the countryside, where everyone contributes to the good of all. Seemingly, because they are old and less important than the stronger villagers, they live further away from the central fires of the warren and are not allowed to keep candles due to some unspoken or unremembered accident which nearly led to a fire. Thus when their communal duties are complete, their evenings are spent in solemn darkness which adds to the melancholy.

They both have little reveries and flashbacks, but their memory is impaired by this mist. They both do agree though that they have a son, who lives in a nearby village, a couple of days walk from them. And thus they seek permission from the village leaders to find him.

Their adventure leads them, in both their trek and in the fragments of recovered memories, to meet sinister monks, witches, the aforementioned boatman, soldiers, an ancient survivor of Arthur’s court and the old King’s nephew (Sir Gawain), an exiled orphan boy Edwin who was bitten by a dragon and thus cursed and finally an accomplished warrior called Wistan, a Saxon, who was tasked with the mission to kill the dragon.

These latter three, Sir Gawain, Edwin and Wistan band together with Axl and Beatrice, and the final scenes culminate with an ascent up to meet the Dragon, Querig.

Throughout the book, little by little, more memories are whispered to Axl and Beatrice. Axl is recognised by both Gawain and Wistan as someone from many decades before. And these memories trickle back to the old couple, such that they end up fearing what they might remember of each other, who they were, what secrets they’d suppressed and might end up hating each other because of it. It’s searingly sad, because they love each other and memories may make that love perish. Their anxiety burns through the pages.

The overall theme though is one of guilt, the power of memory, revenge and war. The eradication of an enemy, the genocide of a perceived enemy is a modern as well as an ancient theme and this unsettles. Sir Gawain is noble, but he carries the burden of the great massacre, a murder of the innocents in the Saxon communities at the end of the war Arthur sanctioned. Although he did not personally take part in killing civilians, he was complicit and didn’t condemn his King. Thus, immune to the effects of the mist, he has adopted the role of Querig’s protector, to keep the dragon’s breath rolling over the land and to keep the memories of hatred suppressed, to ultimately keep the peace. At times his character appeared slightly unhinged, it wasn’t clear if Ishiguro wanted to portray some ambiguity in that, with the secrets he carried and his venerable age contributing to some form of dementia or madness. In other ways he may have adopted this persona as an affectation, to maintain the charade that his mission was actually to topple Querig and not protect her, and thus the populace saw him as a doddery old fool on a fool’s quest.

Axl also finds memories which hurt his heart, he was an important knight himself, “the knight of peace” and ultimately he was betrayed in this massacre, retiring into ignorant obscurity and hard work.

Wistan also carried a burden. He grew up with Briton’s as a child, trained with them, but he was a Saxon. And his Saxon king wanted the dragon dead, so the memories of anger would come to the fore, and thus it would lead to an uprising where the Saxons would deliver brutal revenge upon the Britons. Wistan is also immune to the Dragon magic and was the perfect choice to kill the dragon, his head would be clear, he would not forget. He wanted to hate the Britons, but he saw Gawain and the old gentle couple as decent folk. And thus, once he would kill the Dragon, he would train Edwin, the boy with the dragon bite, to be his protégé.

I won’t spoil the ending if you’ve read this far, I won’t say whether Axl and Beatrice find their son, or whether the dragon gets killed. But it is tragic and heart wrenchingly sad. It’s not a fantasy book. It’s a book about people, about love, regret and the aftermath of war, set in a fantasy setting. A boatman narrates the final chapter, where the ailing couple look to end their journey over a body of water. It’s left open to make your own assumption about what happens to them, or whether they, or their love survives.

But I definitely recommend reading it.

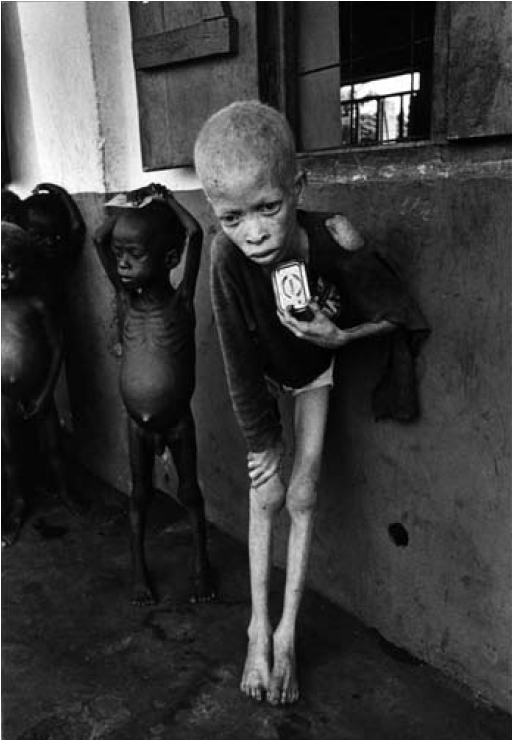

(photo of this photo from thedrum.co.uk)

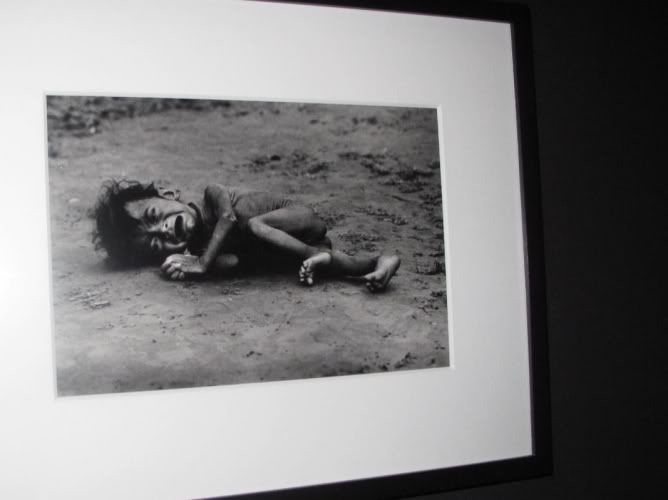

(photo of this photo from thedrum.co.uk)