As part of my birthday we spent yesterday morning at the Imperial War Museum, where we’d bought tickets to see the Don McCullin Photography Exhibition, Shaped by War. It’s a major chronological retrospective covering his social history/poverty and commissioned photography work in the UK and in various war zones around the world.

I have to admit I only knew a little of McCullin’s work (and photography in general) prior to visiting, but I’ve always admired the starkness of human suffering captured in that shutter moment and I always think of the subject and photographer when I see an image which drags out an emotional response. What they were feeling? Whether they survived? Where are they now? Are they happy?

But not knowing much made the experience more forceful, more hard hitting. The first thing to say about McCullin is he’s in his late seventies, he lived through the war years, through poverty and rationing, through evacuation from Finsbury Park, North London. He has felt that hunger in his belly which many of us born in later years will have no concept of.

People from villages and small towns often say that they are proud of the sons and daughters of their region, when they go on to make a success of themselves. Although London is a big city, there still exists some sense of connection and community to an area within it, it may be a nostalgic or romantic vision of it (McCullin himself describes the area as tribal and violent when he was a young adult), but I still cling to some connection and love to where I’m from. Hence, having grown up in the area myself, I felt a sense of pride for Don. Here was a local working class lad who’d contributed so much to photo-journalism and to the world.

It all could have gone wrong for him though, he may have dumped photography, he pawned his camera, but his mother sensibly got it back for him.

In the thirty minute film which is shown as part of the exhibition (see extract below), McCullin comes across as being haunted by the sense of making a living through tragedy. The first tragedy which got him into a career in photography was the murder of a policeman by a north London gang. As he was an associate of a gang himself, he took photos of his friends, he sent them to the Observer and they published them. A window into this (probably) hidden working class world of 1950s urban violence must have fascinated the broadsheet buying public. And that kick started his career.

He doesn’t claim he’s a good guy, and in no way is he a bad guy… there are times when he personally performs great feats of courage or dignity (carrying a wounded G.I in vietnam), there are other times when he says (I paraphrase) he feels repulsed by his feelings towards war, needing it and being enthused by it. It’s an uneasy and unsettling ambivalence, balanced between revulsion and guilt and the absolute conviction of making sure people had a voice in the world, that tragedies would be brought to the public attention.

In addition, he has a deep sense of value for his work, he sheds this peculiar British notion of self effacement, denying or putting down value in your own work. He positively knows his work is excellent, he has invested so much in it, so much skill and feeling, but in no way does it come across as an arrogance, or a blind spot to some hidden weakness. He puts everything into it, he wants us to feel, to become involved. His weakness is one which he is painfully aware of, the guilt he carries for what he has seen and photographed. I suspect he feels this pain every day of his life.

His mistrust of humanity stems from what he has seen. As he states in the interview, he keeps his loved ones close of course, but witnessing such unimaginable horror has made him suspicious to the point of avoiding human contact it seems. In recent, non war related work, he seeks solitude through the photography of landscapes, in what he describes as healing. He wants people to fall in love with these photographs. And in the exhibition, after the harrowing images of war, there are some beautiful landscape images which appear gently at the end, a kind of reflection, a small balm, a little reminder that there is beauty in the world.

But, what one man can inflict on another without any mercy or compassion has forged him. His story of his experience in Vietnam sounds like hell on earth. Being surrounded by corpses, sleeping and waking up finding you’d inadvertently slept beside a corpse, jumping into a hole to hind only to find you are sitting on the belly of another corpse, but still maintaining an ability to take photos. It shook him, drove him to battle fatigue, it would have tipped most people over the edge, whether they were fighting men or not. His image of an American solider, having been badly wounded in both legs is one he describes as reminiscent of one of the most iconic images in the western world. That of Christ being brought down from the cross by his loved ones.

McCullin’s has been quoted as saying : “I am a professed atheist, until I find myself in serious circumstances. Then I quickly fall on my knees, in my mind if not literally, and I say : Please God, save me from this”

And it’s not hard to imagine investing frightened prayers for salvation when faced with such chaos and murder all around.

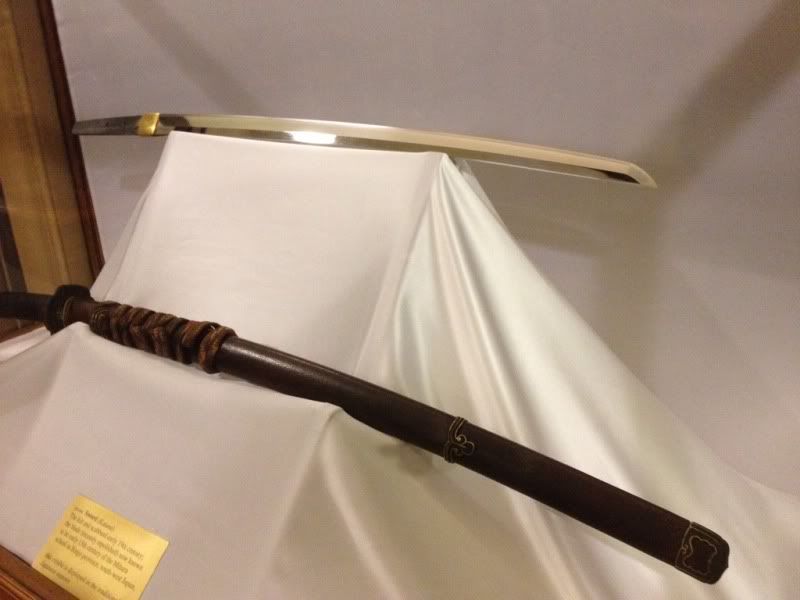

Pic I took of McCullin’s camera which copped a bullet for him. And it still works!

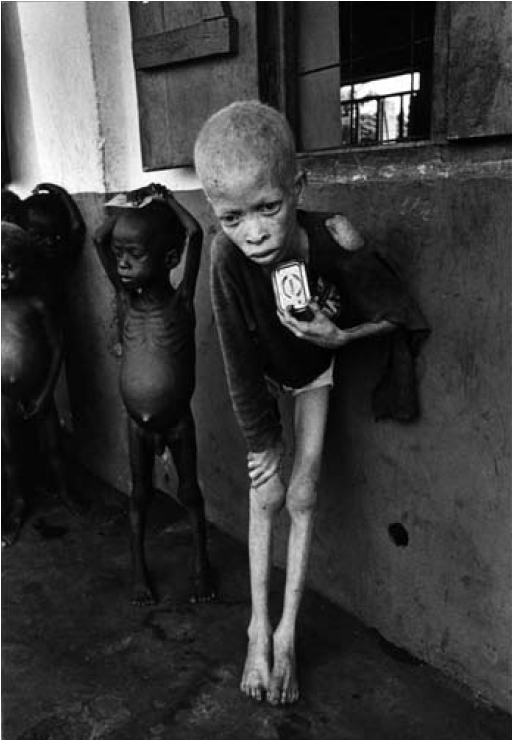

I have to say, going to this exhibition, you cannot be anything other than emotionally involved with the suffering and sadness he has captured. Not just because of images of fighting, but because of images of the victims of war. The hollow shell of the fragile oprhan albino boy from Biafra, not only starving, but shunned because of his condition, dressed in rags.

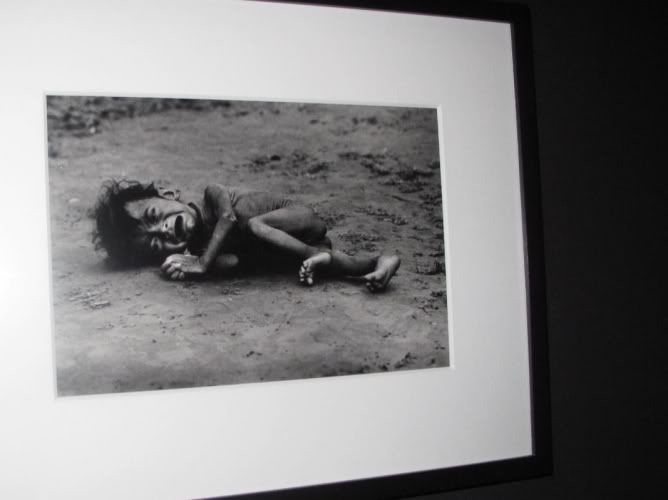

Or, the picture of the abandoned child in Bangladesh in 1971. This child would be about the same age as me. I haven’t stopped thinking about him or her since looking at this photograph.

(photo of this photo from thedrum.co.uk)

(photo of this photo from thedrum.co.uk)

Finally, the final part of the film “The Darkness in Me” where Don McCullin talks of his later years and finding peace. It contains some disturbing, but also beautiful images as he talks about overcoming or at least controlling the darkness in him. The other three parts are also on youtube.

Shaped by War is on until the 15th April.

image from bbc website

image from bbc website (painting by Boom Mee)

(painting by Boom Mee) (by Bakhari)

(by Bakhari)

(wikipedia image)

(wikipedia image)